With immense effort, mason spiders construct elaborate mounds over many hours. Mounds protect their eggs from predation and parasitoids, but only for a few days. We investigated the conditions that lead to the evolution of this unique behavior.

Nests are crucial to the survival of offspring and reproductive success of the animals that build them. However, the benefits of nests are not static through time. From the day they are constructed, conditions inside and outside of the nest are changing because of things like developing offspring, fluctuating environmental conditions, and changes in predator populations. For many species, nest benefits decrease over time until reaching zero when offspring hatch or fledge. The nests of mason spiders are different. Despite requiring hundreds of collecting trips and many hours to construct, mason spider mound nests are destroyed by rain after only a few days, remaining less than 5% of the time offspring occupy nest-sites. Why do mason spiders go through such effort to build a nest that only remains intact for a small portion of the time that offspring inhabit nest sites?

Mason spiders (Castianeira sp.) are wandering spiders of the northern Rocky Mountains that cover their egg sacs with elaborate mound nests. Mounds are made of hundreds of pebbles, leaves and sticks and held together with silk. Mason spider offspring inhabit egg sacs at nest-sites for up to 7 months, including through winter. However, mounds are regularly destroyed by rain after only a few days.

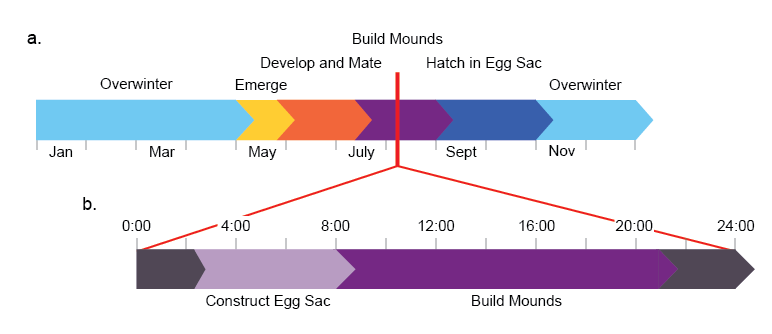

Timeline of mason spider activity over a year (a) and on the day of mound-building (b).

By experimentally removing mounds from egg sacs at different time intervals we found that mason spider offspring face mortality due to predation, parasitism, and fluctuating environmental conditions. Mounds benefit offspring by greatly reducing mortality due to these factors but only in the first 10 days after they are constructed. Additionally, we found that the time between rainfall events has little variation across months and years suggesting that mason spiders may construct mounds to last an optimal duration given environmental conditions.

Funding

Meg and Bert Raynes Wildlife Fund

Acknowledgements

Thank you to thank Blakeney Spong, Blair Loughrie, Sarah Knight, Daniel Stelling, Hayes McCord, and Rip Lambert for providing housing and support during the field seasons in which this work was conducted and the Elias lab members for their many helpful comments and contributions to this project.

Photos of mason spiders by S.J. Karikó, PhD with support from Canon USA.

All photographs and videos by Maggie Raboin unless specified.