Inaudible Noise Pollution of the Invertebrate World | Acoustics Today

“Inaudible Noise Pollution of the Invertebrate World” by Maggie Raboin, Acoustics Today

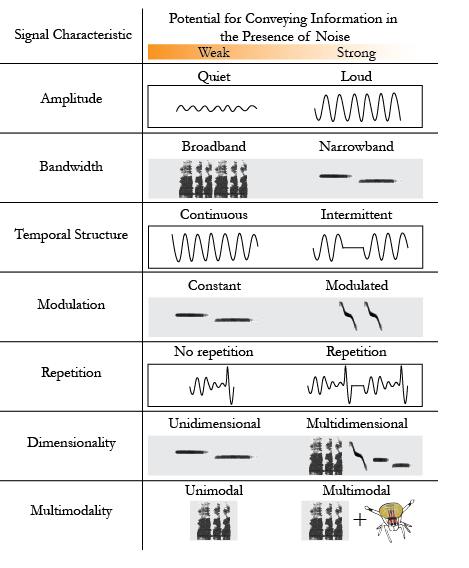

Anthropogenic sound is widely recognized as an issue of environmental concern (Shannon et al., 2016). Produced by human activities like those associated with urbaniztion, economic development, transportation networks, and recreation, anthropogenic sound now penetrates some of the quietest places on Earth (Buxton et al., 2017). In fact, over 60% of US protected lands experience noise levels double those of background noise, despite their distance from major metropolitan areas (Buxton et al.,2017). For vertebrates, the consequences of noise in natural landscapes have been found to be multifaceted, impacting mating, movement, predator-prey dynamics, and physiology (Shannon et al., 2016). However, research has mostly focused on the impacts of pressure waves on vertebrates, with the impact of anthropogenic sound on invertebrates and the acoustic modalities they rely on (mainly particle motion and substrate-borne sound) remaining largely unstudied.

Indeed, when evaluated in 2016, only 4% of the work on the impact of anthropogenic sound on animals had been on invertebrates, despite their comprising 97% of species on Earth (Shannon et al., 2016). However, recent research investigating anthropogenic sound and invertebrates suggests that the impact of noise on invertebrate behavior, physiology, and communities is likely diverse and complicated. The goal of this article is to introduce readers to invertebrates, their bioacoustics, and the potential effects of anthropogenic sound on invertebrates.

Inaudible Noise Pollution of the Invertebrate World – Acoustics Today, Volume 17, Issue 2

‘Woven Together Art and Arachnids’ Art Exhibit | National Museum of Wildlife Art

Woven Together: Art and Arachnids is a collaboration between the National Museum of Wildlife Art and Jackson Hole community members. This exhibition was inspired by and features Beyond Beauty, an episode from the Museum’s Bisoncast video series that stars local spiders—including the recently-discovered mason spider (Castianeira sp.)

National Museum of Wildlife Art

Links

- Woven Together finds connection, beauty – The Jackson Hole News & Guide

- Museum Short In Film Fest – The Jackson Hole News & Guide

- Record setting summer at the National Museum of Wildlife Art – Buckrail, ArtFix Daily

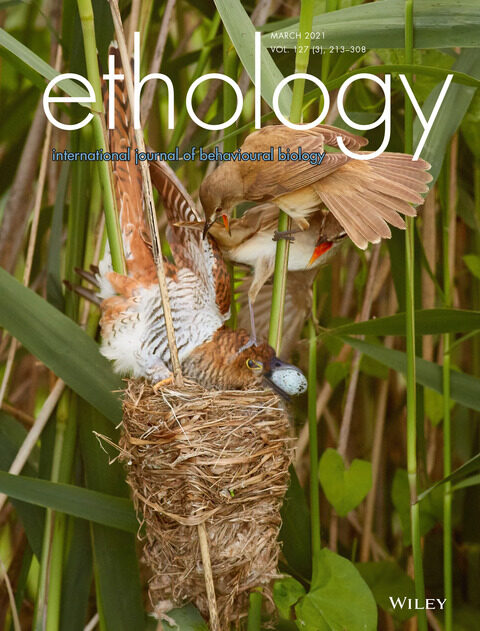

Built to last a day: The function and benefits of spider mound nests – Ethology

Built to last a day: The function and benefits of spider mound nests Maggie Raboin, Damian O. Elias Ethology

Abstract

Nests are crucial to the survival of offspring and reproductive success of the animals that build them. These benefits are subject to change over time due to fluctuating conditions inside and outside of nests. For many species, nests are assumed to benefit offspring until they disperse and therefore, nest destruction prior to offspring dispersal results in reduced reproductive success for parents. However, the consequences of nest destruction to reproductive success, or lack thereof, remain largely unstudied across diverse taxa. Here, we experimentally investigate the function and benefits of nests of a mound-building spider. Mason spiders (Castianeira sp.) are wandering spiders that build intricate nests (mounds) on top of their egg sacs. Their offspring inhabit egg sacs at nest sites for up to 7 months, including through winter. We find that despite requiring hundreds of collecting trips and many hours to construct, mason spider nests remain for a small portion of time that offspring occupy nest sites. Our study finds that nest benefits change over time, likely explaining this dynamic. Nests greatly reduce the rate of predation and parasitism of egg sacs by 19.1% and offspring mortality within egg sacs due to abiotic factors by 19.9%. These effects are only present the few days following nest construction. Our study illuminates the idea that nest destruction does not always result in reduced reproductive success for nest builders. We suggest that nest durability, the ability of a nest to withstand environmental conditions, may be subject to natural selection and a critical, yet understudied, aspect of parental care.

Built to last a day: The function and benefits of spider mound nests – Ethology

Research Funding

Bisoncast Video Series: Beyond Beauty | National Museum of Wildlife Art

Who decides what is beautiful and what is valuable? Can a creature that crawls into our nightmares also be vital for our survival, and, even charming?

Bisoncast is an award-winning video series produced by the National Museum of Wildlife Art in Jackson, Wyoming. Each episode features a closer look at art from the Museum, and considers cultural and historical influences, current relevance, and connections to the natural world.

Last summer, I was fortunate to spend a day shooting with representatives from the Museum and the film crew from Teton Gravity Research at one of my field sites in the greater Yellowstone area.

Beyond Beauty Awards

Review of Anthropogenic Noise and Invertebrate Bioacoustics Published

Our latest paper was published in the Journal of Experimental Biology! In this paper, we use literature on invertebrate bioacoustics to outline the potential impacts of anthropogenic noise on invertebrates. While researching and writing this Review, two overwhelming themes emerged. First, acoustics are incredibly important to terrestrial invertebrates – the ways in which they use sound are almost inconceivably diverse, both mechanistically and ecologically. Second, because the ways that invertebrates and vertebrates sense and use sound are so different, an appreciation of human-created noise in the natural world requires a recognition and more full understanding of invertebrate bioacoustics.

Check out the full paper here.

Feature in JH Style Magazine

You can read the full article by Jill Thompson here.

Spiders! Interconnectedness exhibit at GTNP

This week, I participated in an art/science exhibit to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the National Parks and honor arachnologist, Herb Levi. The exhibit was put together by Sarah J. Karikó and took place in Grant Teton National Park and at the National Museum of Wildlife Art. I was excited to be paired with the amazing artist, Jenny Dowd, who created works inspired by mason spiders and other spiders of Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem.

Feature in Jackson Hole News & Guide

Check out the full article by Mike Koshmrl here.

Boyd Evison Fellowship 2016

Thank you to the Grand Teton Association for awarding me the Boyd Evison Fellowship for my proposal “Spider Blood Runs Cold: Implications of Winter Climate Change for Overwintering Arthropods in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem”! I look forward to getting back Jackson, WY to conduct this research.

Check out the National Park Service press release here.

Open to Discovery

Published in the Jackson Hole News & Guide June 3rd, 2015

You can find me on the side of the road most summer days. The sloping gravel that remains when man cuts through mountain landscapes to build asphalt lanes is often a good place to find certain arthropods.

As I walked along Highway 89 in mid-August 2011, I noticed a small black and red spider scurrying along the gravel. The spider was carrying a pebble half the size of itself, and without a closer look I would have mistaken it for an ant.

But sure enough, eight legs! My curiosity took over. What was this spider doing? And where was it going? I followed the spider with my eyes as it climbed a rock and placed the pebble on top. Over the next few minutes the spider gathered more and more pebbles, stacking each piece of sandstone on top of another, forming a cairn-like mound and sealing each addition in place with silk. When it was finished, there stood a mound 10 times the size of the spider, equivalent to a human building a gravel pile 20 feet tall in an hour.

I pulled out my phone and took a video of the spider at work. I was a wildlife biology student at the University of Montana and a budding naturalist. I was hoping to use the video to ask my professors what kind of spider would spend its time performing this exhausting task. I had never seen anything like it, but at 21 years old I hadn’t seen much and was sure a little digging would lead to an answer.

On that day I didn’t know that giving my inner curiosity a moment of attention would open up the doors to discovery and graduate school at the University of California, Berkeley. In the four years that have passed I have discovered that the tiny spider, now called the mason spider, was previously unknown to science and that at least for now is the only known spider in the world that builds mounds.

The Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem has attracted naturalists and scientists for more than a century, so it might surprise you that discoveries are still being made here. In fact, not one national park in the United States has been systematically searched for wildlife organisms, let alone all species including plants and fungi. In the past decade, hyped “bioblitz” programs have exposed just how much we have to learn from our national parks (A 2009 Yellowstone bio-blitz uncovered more than 1,100 new species). Still, bioblitz programs are few and far between, and funding for scientific field exploration is waning.

Today science relies on amateur naturalists to make discoveries. You might not consider yourself a naturalist, but if you make daily pilgrimages to forested trails and blue-sky vistas or can identify that a magpie destroyed your trash, you qualify. Naturalists abound in Jackson Hole. We often romanticize men like Charles Darwin and Henry Walter Bates, travelers and naturalists of the 19th century, who discovered new spaces and the species that inhabited them, but we shouldn’t treat discovery as a thing of the past. Each moment spent in the open spaces of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem is an opportunity for discovery: of species and of self. We should pay attention to each flash of curiosity because for as much as we know about the ecosystem there is much more that has yet to be discovered.

This summer I will embark on another field season in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem as a part of my graduate work at UC Berkeley. I hope to reveal why mason spiders build mounds and how this unique behavior evolved.

Next time you stop for a break while hiking, look for a tiny pebble mound — the sign of a red and black mason spider. Or better yet, put your Darwin hat on, keep your eyes open, and have confidence in your curiosity. You just might discover your own fascinating species that is new to science.